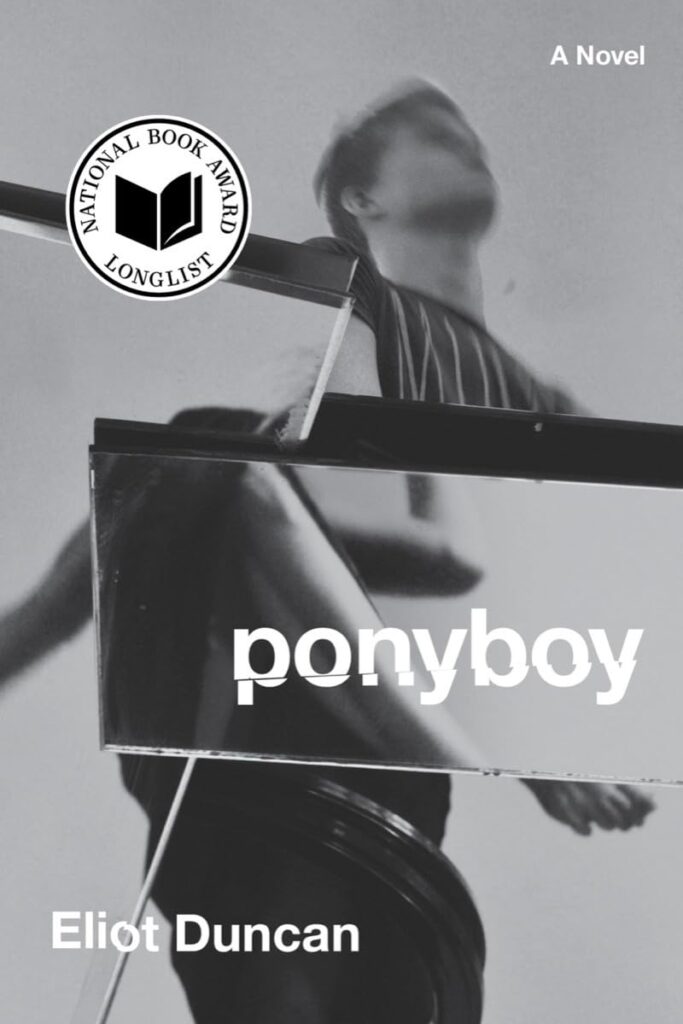

Ponyboy: Intimacies & Ecstasies of a Transmasc Jerk

The best book of 2023.

by Cole Stapleton

‘Chop off my chest

you’re my surgeon just

cut me open

pull out the tissue and

feed it to your dog

he’s a good boy’

‘Chop off my chest

you’re my surgeon just

cut me open

pull out the tissue and

feed it to your dog

he’s a good boy’

Certain readers will be familiar with the exhilaration I get when I encounter a good book about transmasculinity (or one that prominently features transmasculine characters). For me it often starts as a private pleasure. I see something flash across an instagram story or hear about a book from a friend, and I rapidly take a screenshot or jot a note down on my phone. A few books come to mind when I think of this specific kind of rush: Confessions of The Fox by Jordy Rosenberg, Paul Takes the Form of a Mortal Girl by Andrea Lawlor, and of course Stone Butch Blues by Leslie Steinberg (a bedrock of the genre).

“Are you wondering how to get here?

Dear Reader, if you are you— the one I edited this for, the one I stole this for— and if you cry a certain kind of tears— the ones I told you about, remember?— you will find your way to us.

You will not need a map.’

– Jordy Rosenberg, Confessions Of The Fox

You might also be familiar with the engrossment and subsequent relief of a text like this crashing into you. Talking with a friend from Germany recently, they told me about their first experience reading On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous: in one sitting, on a train home from holiday. They described the hooks of Ocean Vuong’s prose sinking into their chest, the urgency and intimacy of the encounter. Queer texts have the power to do this to us—to name something otherwise obscure, to speak our lives into clarified existence as they spread before us on a page. Holding us from first page to last. Ponyboy had this effect on me.

Eliot Duncan had me wrapped around his finger from the first moments of Ponyboy. We meet our nameless protagonist in Paris sometime in the mid 2010s, snorting lines of blow off of a coffee table, lost in a trans aimlessness that felt instantly familiar. Desperate for connection: with his girlfriend, his family, and his own body—we follow as Ponyboy emerges into the reality of his trans identity. As he spirals in and out of addiction, and towards himself, Ponyboy gains the strength to choose his name, and proceed through the world authentically.

This book is overflowing with the specific kind of erotic energy that makes trans men so hot. It’s direct and insightful, the prose delivered clearly at first and then sliding through your fingers as the plot dips into reverie. The sex is tender and real, the pain of Ponyboy’s loneliness is tangible. Ponyboy has an auto-fictitious quality that is neither hidden nor named – you are close to Ponyboy (later Eliot) the whole time. The text feels personal, and a kind of generosity peaks through as the narrative quiets in the later sections of the book. As Ponyboy arrives at rehab a new voice emerges, a character who can confront himself. Ponyboy metamorphosizes through his addiction, perpetually in transition.

I was lucky to attend the release party/reading for Ponyboy in Berlin this summer. The center chunk of the book takes place in Berlin; mostly in a drug laced fugue. Maybe it was because I came to the reading on the heels of a night with god at Berghain, or the microdose of mushrooms I took before biking there – but the energy percolating on this night made Ponyboy’s world even more real to me.

The other readers that evening, Alvina Chamberland, Ryan Ruby, Rebecca Rukeyser, and Saskia Vogel were all fucking fantastic. The conversation orbited ideas of sleaze (a prominent theme in Rebecca Rukeyser’s amazing book The Seaplane on Final Approach), what it meant to be a ‘transmasc jerk,’ and addiction.

During the Q&A I asked a question which I didn’t quite articulate properly–something about the connection between addiction and transness. What I meant to say was that Duncan had queered the addiction narrative in Ponyboy. For those who have lived through addiction ourselves or with a loved one, we know that the curves of dependency are rarely well depicted. Often we are delivered stories that exist in a binary: sobriety or death. But Ponyboy’s emergence into a delicate sobriety and (speedy, but short lived) relapse at the end of the book present him with a new possibility at life, just as his transness does. In the evasion of this binary Duncan gives us a more honest understanding of addiction and the people who live with it.

When he answered my question, Duncan said simply: “Some people are trans, and some people are addicted to drugs, and sometimes people are both.” The directness of this response struck me. Part of Ponyboy’s magic is Duncan’s resistance to romanticizing the uglier parts of growing up. But then again, there is an undeniable lightness to the weaving of Ponyboy: a potential for doom that is skillfully avoided, a comfort readers can carry with them that Ponyboy will survive to the next chapter. Ponyboy offers us a trans narrative that carries the heaviness of its job and yet celebrates life. Right now, in the year of our lord 2023, that feels like a miracle.