An Interview with Ariel Dorfman

Ariel Dorfman discusses The Suicide Museum, literary doubles, Henry Kissinger, and more.

by Dylan Cloud

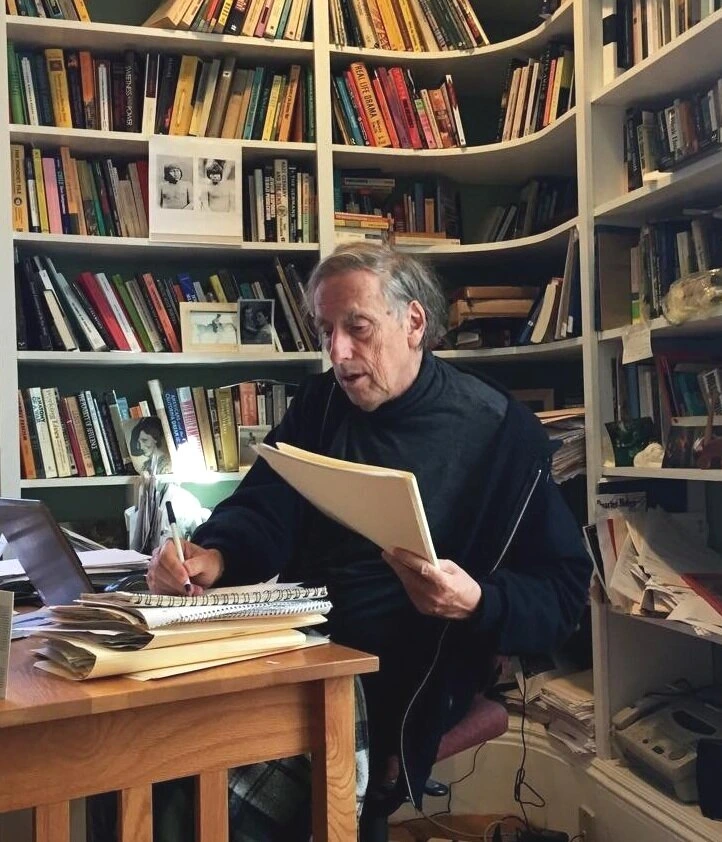

There are few writers working today whose body of work displays as much literary and political intelligence as novelist, playwright, poet, and activist Ariel Dorfman. Born to Jewish immigrants in Argentina in 1942, he lived for ten years in New York before McCarthyism forced his family to relocate to Chile. There, Dorfman would go on to work as an activist, taking part in the ‘peaceful revolution’ of Salvador Allende’s Unidad Popular and eventually serving Allende’s government as a cultural adviser. His 1971 book How to Read Donald Duck provided an anti-imperialist analysis of popular Disney comics, and was read widely across Latin America. Following the Pinochet coup, Dorfman and his family fled Chile and continued to work tirelessly to provide support to friends, artists, and activists who remained behind. Dorfman would spend several decades in exile, eventually ending up in North Carolina, where he still teaches at Duke University today.

The release in September of The Suicide Museum, Dorfman’s newest novel, coincided with the 50th anniversary of the US-backed coup in Chile, which toppled the Socialist government of Salvador Allende and kicked off the nearly two-decade dictatorship of right-wing demagogue Augusto Pinochet. The Pinochet government, of which Dorfman was an outspoken critic, was responsible for the murders and disappearances of tens of thousands of Chileans. Pinochet’s right-wing economic policies, conceived in Milton Friedman’s University of Chicago think tanks and incubated according to the directives of Henry Kissinger, wreaked havoc on the Chilean working class, and, as Naomi Klein argues in The Shock Doctrine, provided a blueprint for Reaganism and the neoliberal economic policies which have defined our present era.

Writing in Spanish and English, Dorfman has built an impressive legacy for himself in both North and South American literature. His work is at once deeply personal and political; The Suicide Museum follows a fictionalized version of himself who is commissioned by an eccentric billionaire to determine whether Salvador Allende’s death was a murder or a suicide. The Suicide Museum finds Dorfman revisiting familiar ground with new urgency; themes of exile, memory, and cultural inheritance are recontextualized in the looming shadow of climate change, which Dorfman views as a kind of species-wide suicide. His other work includes Death and the Maiden, The Last Song of Miguel Sendero, Heading South, Looking North, Widows, and many more. Readers who dig into Dorfman’s work will be richly rewarded, finding not only a dazzling display of literary talent, but an inspiring vitality for activating the political potential of literature.

Gryllus: Everywhere one looks in The Suicide Museum one finds doubles. The twins Abel and Adrián. The conflicting accounts of Allende’s death. The fictitious and the real Ariel Dorfmans. Why is the double such a compelling figure for you, showing up not just in The Suicide Museum, but across your other work?

AD: You are right that there are doubles everywhere in the new novel and I welcome the chance to explore how this theme appears in my previous work. Such an obsession must come from something deep and structural in my life. As a child, I always craved a twin brother, to the point of wondering if I had not been adopted and there was another “me” out there waiting to be discovered. Maybe that’s why Twain’s The Prince and the Pauper had such an impact on me – I even changed my name from Vladimiro to Edward, a process I describe in the memoir, Heading South, Looking North. And when I was a seventeen year old freshman at the Universidad de Chile, I wrote an essay (115 pages instead of the 6 that the professor had required) on doubles in literature (Poe, Hoffmann, Hawthorne, Dickens, James, Dostoyevsky, Stevenson, Cortázar). Not strange, then, that twins should appear so frequently in my fiction (think of Widows and The Last Song of Manuel Sendero, or the phantom doppelgänger in Darwin’s Ghosts and the alter ego censor in the story “Reader” that I then made into a play). And in a novel that thus far has only been published in Spanish, Murieta’s Footsteps (to appear in English, I hope, in 2026) a pair of identical twins represent the bifurcated ways in which the oppressed Californios of the 19th century could react to being incorporated into the United States, be rebelling or by adapting. This compulsion to return, again and again, to twins, may have roots in my perpetually exiled and doubled (and duplicitous?) existence, changing lands and languages and allegiances. Even so, what predominates in my fiction is not someone accompanied by a counterpart, but rather a solitary male narrator who is searching for a protector, a father figure, an elder brother. Come to think about it, what I like about The Suicide Museum is that this novel delves into both doubleness and loneliness as essential to our human condition, with the implication that they may be complementary mirrors of the same quest.

Gryllus: Another major theme of your work is memory, and the projections and shifting realities of the past. You yourself were named Chile’s ‘Ambassador of Memory.’ A line in The Suicide Museum that I love and keep coming back to: ‘those in power are always trying to turn the page.’ How are you thinking about memory when you sit down to write?

AD: All my life, over and over, I have been a witness to the constant erasing of the past by those in power, an active forgetting of what could disturb the “official story”, effacing the experiences, memories, suffering and struggles of vast masses of neglected protagonists and victims. A considerable part of my work, both literary and as a human rights activist, is opening spaces for those alternative voices, suppressed by the victors and the owners of the means of communication. This fierce moral imperative to remember is never, however, straightforward, because I am also aware that, even if the insurgent past is brought back, it is still subject to varying interpretations and recreations. The Suicide Museum tackles this dilemma from many angles, not only regarding the central enigma of whether Allende was murdered or if he died by his own hand, but by deploying how the choices of the main characters are determined by a fluctuating, evasive series of yesterdays. Memory is complex and that is always paramount in my mind as I begin writing anything, memory as a country being disputed endlessly. Take the case of Paulina who, in Death and the Maiden, has suffered terrible abuse. Her demand for justice and the recognition of what she has gone through should never be denied or forsworn–she is by far one of my favorite characters – but that does not mean that her path forward, towards the truth, will be an easy one. No matter how much one is on her side as an avenging angel, the play lays out other competing claims to the truth. In Allegro a novel to be published next year, the narrator – none other than Mozart! – sets out to investigate conflicting versions of the death of Bach and Handel. How he resolves this, how he keeps his ethical compass as he navigates the labyrinth of past deceptions and ambiguities, is what affords drama to that story. One could venture that a similar aesthetic tension permeates all my work.

Gryllus: Earlier this year you wrote a piece for The Atlantic about a recent investigation which concluded that the cause of the Chilean poet Pablo Neruda’s death was not cancer, as previously reported, but that he was likely poisoned by the Pinochet government. This decades-old question has parallels with the central mystery of Allende’s death in The Suicide Museum. Can you talk about the significance of the truth about Neruda’s murder for your book and for Chile?

AD: Judicially, the case of Neruda’s death has recently been closed, just as occurred with Allende and former President Frei, who also died under shadowy circumstances during the dictatorship. Much remains murky and uncertain, however, in all these instances. The problem is that Pinochet’s government committed so many crimes and lied so incessantly about them that it is now impossible for Chileans today to distinguish between what is true and what is false (sound familiar?) and this poses a tremendous challenge for moving forward to some form of national unity and even reconciliation. When I began writing The Suicide Museum, I did not know what conclusion the narrator would reach as he investigated the circumstances surrounding Allende’s last moments. The solution which he comes up with (and I will not ruin the pleasure of readers finding out on their own what that is) depends not only on objective evidence but on the needs of that narrator and his friend, Joseph Hortha. I wasn’t clear, when I wrote the ending of the novel, why I had decided on that ending, but, in retrospect, I believe that, by not giving an absolutely clear resolution (as happens in typical thrillers or murder mysteries), I was being true to the fragmentation of Allende’s nation which today is as divided as it was fifty years ago. And I also hope that the way in which I presented these dilemmas regarding how we find the truth when a country is so fractured will resonate beyond the borders of Chile, particularly in the United States, my second home, that is also desperately trying to deal with its own past, recent and remote.

Gryllus: In 2020 you published your first book for children, The Rabbit’s Rebellion. What made you want to write a children’s book?

AD: The book was, in fact, written in Spanish in the late 1970s, when I was exiled in Holland. It has, since then, been translated into over a dozen languages and had a British edition many years ago, but only appeared in the States in 2020. And I’m delighted that a major animated feature based on my recalcitrant and magical rabbits is in pre-production, so its message may soon reach a vaster audience. Originally, I wrote the book because I was desperate that the young kids of Chile (and other Latin American countries suffering dictatorships) were being contaminated by the authoritarian government ruling their lands and their lives. As I could not overthrow those regimes, I subverted them through the tale of a Wolf King who decrees that rabbits don’t exist and who, nevertheless, cannot stop those rabbits appearing and reappearing in photographs, thanks to a little monkey girl who will not be cowed by tyrannical decrees. It is, ultimately, the victory of the imagination over fear – something we all need to believe is possible, especially children, with their wild creativity. This is not, by the way, the only children’s book I have written. There is also one about a boy who makes friends with a special bear (alas, only published in France) and many others that have yet to see the light of day.

Gryllus: Just a few days ago Henry Kissinger, the architect of the 1973 coup which led to Pinochet’s brutal dictatorship, the deaths of tens of thousands of Chileans, and your exile, finally died at the regrettably old age of 100. How did you feel when you heard the news?

AD: My first reaction was astonishment: like the dictator in García Márquez’s Autumn of the Patriarch, it seemed as if Kissinger would never die and continue plaguing us for centuries to come. But once I realized that it was true, what struck me – as I expressed it in an op ed in The Los Angeles Times – was that he was going to his grave without having been held accountable for the numerous war crimes he committed. I contrasted his funeral and the fawning eulogies he was sure to receive with the fate of the “desaparecidos”, not only of Chile, but of so many other nations he devastated (Vietnam, Cambodia, East Timur, Cyprus, Argentina, Uruguay, not to mention his support of apartheid in South Africa and his betrayal of the Kurds). It mattered to highlight the disparity between Kissinger being laid to rest regally and the lack of even a small piece of earth for the missing of Chile and the world. I urged that we keep those dead victims of his alive, that we help them haunt his future. An example, by the way, of my mission to be that “Ambassador of Memory” which you mentioned in another question. When we forget the dead, we are eradicating our own selves, allowing future generations to forget us, breaking the link between ancestors and descendants, the chain of hope of our humanity. This is the most profound message shining from The Suicide Museum.