De-Creation

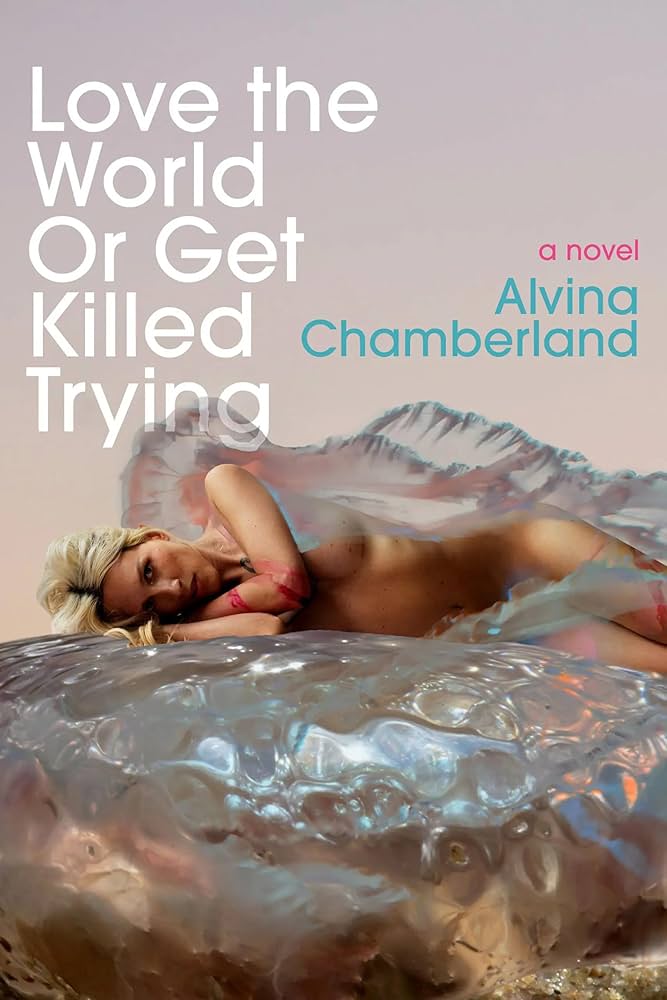

Cole Stapleton reads Alvina Chamberland’s Love the World Or Get Killed Trying.

by Cole Stapleton

There is a series of improvisational ‘technologies’ created by choreographer William Forsythe that I find useful for both dancing and writing. One technology, Decreation, shares a name with Forsythe’s 2009 ‘artificial opera’ (which itself takes its name from Anne Carson’s 2005 collection of poetry and essays). Decreation challenges its dancer to trace a pathway backwards through space: invert the dance, reverse each gesture, and in doing so reshape the course of movement entirely. It is a prompt to un-become. Resisting the world’s constant pull of forward motion reveals the intricacies of connection between dancer, choreographer and audience. Reading Alvina Chamberland’s Love the World or Get Killed Trying, I discovered a similar manual for un-becoming.

In Love the World or Get Killed Trying, we crawl with Alvina through the anticipatory crisis preceding her 30th birthday. The narrative is a travelogue of relentless self-investigation, unrestrained by borders or boundaries. Through Reykjavik, Berlin, Paris–ribbons of memory and soliloquy steadily interrupt the chain of action; it is the braid of these stark, often humorous interjections which brings us to the heart of our quest: how (and where) can Alvina find love? Not just the love of a man (though this does constitute a significant portion of her quandaries), but an inner love with which she is determined to meet the world.

Each station of Alvina’s “non-guided travelogue” provides not a map, but a challenge. The register of confrontation we’re met with along the way is both an indictment and an invitation. In city after city, memory after memory, Alvina encounters transmisogyny and harassment–this violence is the inverse of Alvina’s love, propelled back at her as she projects it outwards. Her monologue guides the reader up mountains, to the dancefloor, into rented rooms and uncomfortable conversations. We feel the pain of her disconnection, we delight in her triumphs. She is going, going–but to ask where is to miss the point. The direction of the movement is not what characterizes the dance.

“Ok reader, I swear this time that this is the last time I’ll tell you about these incidents. I will thereby be providing you a comfort I simply do not have. Unless you’re like me, and if so, I hope we can hold each other as we break down so the flood won’t sweep us away.”

Rather than write a traditional review of the work, I prefer to react. I think Alvina will understand. Truly, the work speaks for (and about) itself. I first encountered Love the World or Get Killed Trying at the Berlin release party for Eliot Duncan’s Ponyboy, where Alvina read the first chapter. Her introduction: ‘I will not put a trigger warning on my life.’ I was captivated–as was the rest of the audience. LTWOGKT would hit me at a particularly tender moment in my own acceleration towards Decreation.

When I was a kid I had the kind of depressive anxiety that craved rules. Structure, play-books, how-to’s. I desperately craved instruction for a world that felt indecipherable. I loved memoirs because they were also manuals. Each was a one-way mirror, a chance to understand how others managed the impossible: existing, being known, having a family, making money, not making money, being an artist, being a woman, being not a woman, etc. Through others’ explanations of their lives, I gleaned validation in my own–there was, as it turned out, some explaining to do!

Now, as an adult-child, I love the moment that autofiction is having. It’s delightful to peel the curtain back on what we all already know about fiction… it’s based on real life! The thinner the level of abstraction, the more I can lean into my literary peeping Tom. More powerful, however, is when the ideas of ‘real’ and ‘life’ become suspended. Much as I might crave it, there is no manual for being. Where other works of self-narrativization trace the course of a subject’s journey to actualization, Alvina’s work invites us in the opposite direction. What if being is overrated?

“I won’t live life to the fullest, I’ll just live. And I won’t achieve! But I will care. Always. And I shall let everything touch me!”

On her journey Alvina is accompanied by a trinity of holy ghosts: Violette Leduc, Vaslav Nijinsky, Sylvia Plath. When Alvina’s ever-tenuous connection to The Moment wanes, she retreats into the web of recognition she has woven of her heroes’ lives: “They’re very impressed that I’m able to get into Berghain. I find it irrelevant. Just as I find it irrelevant that my beloved authoress Violette Leduc knew Camus, de Beauvoir, Genet, Sartre, and Cocteau… Now, together, we crave miraculous impossibilities which are easily achieved in our divine worlds. Yes, Violette & I are nothings clinging to everything! So these straight men had better watch out!”

I spent 3 weeks of last summer with Leduc’s La Batarde at an artist residency under Mount Vesuvius. Alvina’s invitation to revisit Leduc’s work caused another realization, one that started churning in the shadow of that angry mountain:

Queer memoir is itself an act of fiction. Narration of this sort is never a passive act. It is a process of taking in what the world knows and sees and its metabolization as an act of survival. It is an achievement to make it out as oneself on the Other Side. There is a kind of exchange in this survival, a threshold of sacrifice required. LTWOGKT dissolves the necessity of compromise, and in doing so also rearranges the question of how to live. Decreation. As contemporary fiction leans into what’s ‘real,’ it’s also wading into a literary tradition that queer writers have been swimming in for centuries.

Memoir, fiction, autofiction, whatever name feels right for the type of work that reaches out at you from the page, grabs you by the neck, and plants a delicate kiss right on your mouth–it’s the work that we need. It’s high time to un-become!