Endless Performance

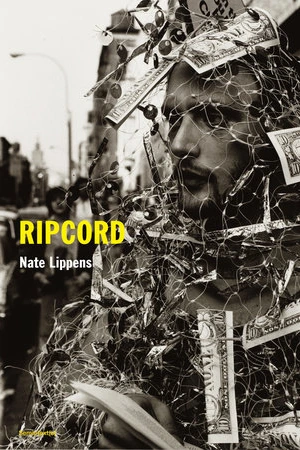

An Interview with Ripcord author Nate Lippens.

by Cole Stapleton

I first read Nate Lippens in 2022, when I picked up his debut novel, My Dead Book, from Burning House Books in Glasgow. My Dead Book is a meditation on aging and survival, an elegy for friends and lovers the narrator has outlived. The novel channels the voices of the dead, assembling a seance-like narrative of intersecting memories. Lippens’ voice is direct, often funny, pulling the reader forward through the gaps and secret tunnels that give the slippery time-space of the novel its structure. In October Lippens published Ripcord, a sequel to My Dead Book.

In Ripcord we gain even more access to the narrator’s inner world. We are shown the details of his dating app profile, his catering job. Friends, work–the repetitions of daily life are interwoven with memories of performance art, collage, and zines from the 80s and 90s. Vignettes of conversations, bus rides, sexual encounters–all refracted through the narrator’s performance of his life.

Nate Lippens was kind enough to speak with Gryllus about Ripcord, performing his life as a writer, and the queer experience of nonlinear time…

Cole: Preparing for this interview, I searched my apartment for my copy of My Dead Book. I went outside to my car to check if I was keeping it in my trunk (because I keep a lot of my favorite books in the trunk of my car). And while I still haven’t found my copy of My Dead Book, I did find my copy of Shock Treatment by Karen Finley – which I also spent a lot of time with in 2022, and is threaded into Ripcord.

“I would work and take my money and head to the East Village to see bands or performances. Karen Finley covered in chocolate and tinsel. Lights caught the shimmer as it shook across the stage. Like a mirror ball. Her voice rose like an evangelical preacher, shill, piercing… I wish I could relieve you of your death.’/ Travel between worlds was punishing. At some point the passageway would close. I knew where I wanted to be, but the other was more likely.”

–Ripcord, p. 94

Nate: Karen Finley was a very important person to me from a pretty young age because I remember reading about her first in the Village Voice. Cynthia Carr, who did the David Wojnarowicz biography and the recent Candy Darling biography, had a column called On Edge in the Voice. They had cover story on Karen Finley and it was a huge scandal within the Voice at the time. There were political writers there–male political writers–who were upset; they felt that it denigrated their overall coverage that she got the cover. To them it seemed juvenile. They didn’t understand what the art was.

I went down to Chicago and saw her at this crazy hole in the wall. And she was being, if not outright banned and blacklisted, harassed. So during the course of her doing the show in this tiny place, the fire marshals come in. And she’s on stage, half-clad, going through this intense sexual abuse monologue.

I believe they had a cop with them. Everybody was so freaked out. It was crazy to think, here’s this performer being disrupted, chased cross country through all of this. And as they were looking around and they were dealing with the arts administrators of this space, she sort of went off-mic and turned to us and said: I don’t have my purse up here, but does anybody have fifty bucks? I’m pretty sure we could pay them off. And I just thought it was incredible. It was really incredible.

Cole: You were 16?

Nate: I was 16, yeah. I saw her in New York probably when I was like 17, around 1987. I’d left home at 15, so I had bounced all around, and it was just this continuous thing of seeing her, and each time being sort of blown away. And although there’s photographs, there’s videos, whatever–there’s just something so specific about being in the live presence of something like that.

In my 20s, I’d been writing. But because I was so outside of any academic thing, I really didn’t understand (probably as a working class person) how to access things. I would send things in, but I didn’t understand, really, the mechanics behind publication. I started doing monologues where I would do an outline, and then improv off of that. And eventually I would record it, and then I would transcribe it, and then make a new outline, and do that over and over again until there was a completed script. And only recently did I think, Oh, I was training myself to write.

Cole: And to perform. Those sound like really incredible performance scores, to record monologue and go back over it.

Nate: That was one of the things I think I got from watching someone like Karen Finley, who continues to perform and just did a performance a few years ago tapping back into all of the rage and grief around AIDS. Performance art was important to me in that period of time, I think.

Those names, at that period of time, were like a passcode. If someone else knew about it, you just were instantly like, Oh, I’m interested in who you are and where you’re coming from, because it did feel like such a small world of stuff.

Cole: Performance feels really central to the (unnamed) narrator of Ripcord. It also feels important to how time is functioning in the narrative. In both Ripcord and My Dead Book, the narrator lives in a constant state of suspension: between waking life and memory, between narrative timelines, and between relationships. Often that suspended state is isolating. “To be the only one with a memory of a story others say never happened is to be crazy.”

Performance art, and performance artists, is a place where the narrator takes refuge and finds the present. Can you speak to how performance situates itself in the way that time is moving in Ripcord?

Nate: I was thinking a lot about that as far as memory within writing, where things are often treated as condensed flashback that gives you backstory. I don’t experience memory like that at all. I mean, very odd things will occur to you at certain times. Or it’s interesting to revisit a memory that a year ago can be very painful, and then a year later you don’t have that same sharpness with it.

“I’m in an abusive relationship with time.”

–Ripcord, p. 18

I think a lot of the performance art from that period of time was really trying to–someone like Karen Finley or Ron Athey–where it’s ritualized. There is a way in which it’s trying to elevate or sort of sanctify some of the suffering that was happening–that was already being treated as numbers or statistics. This wasn’t documentary in the way that someone else would be an outsider, taking a photo or taking a video. It’s somebody from inside that world, proclaiming and elevating it.

It definitely influenced my ideas of trying to present time. Also, trying to present memories in a way that didn’t just feel like documentary or backstory or as some sort of exposition for the narrator. I wanted him to be a choral voice.

Maybe that’s what adds to that extra fogginess between past and present–being able to draw on those different voices.

Cole: I really feel that as a reader–that flashback in your work is never backstory. The character is experiencing time in three dimensions, just like we do. Narratively we are sort of more fractal. So I think your work is operating in a really different way. And in a way that I think links it to performance work in a way that is really beautifully elaborated on in Ripcord.

If performance is the narrator’s tether to the present, then collage seems to be the narrator’s connection to his history, his memory, his ghosts. In particular, there’s a relationship built with collage and with the narrator’s friend, Charlie, who holds onto things: ephemera, magazines, zines, records, photos… And it’s clear that collaging is part of the construction of Ripcord and My Dead Book.

Nate: I definitely came of age during a period of time of zines that people made at Kinko’s. Wheatpasting our own posters for band shows and performances. It was an X-acto knife and a glue stick. So it had always come very naturally to me.

The thing with the collage is that I was able to take a piece of something from that earlier novel and go, Oh, this would really work without these two pages. So really I was just cannibalizing some old work and then writing–they worked as things to prompt me to write, and then just pull really different pieces in.

I had gone through a period, probably 10 years ago. I had written a pretty conventional novel and was shopping it around, and having difficulty with it. At some point I set it aside–and when I was looking at it later, I thought, there’s a problem here. There’s just too much realism.

I don’t experience life as moving in and out of a room. It feels like I tried to write a novel in the way I thought a novel should be done instead of writing the way I actually think. So a lot of the process of My Dead Book was learning how to not be ashamed of my mind. To not feel like a Martian because I moved through time in the way that I did.

For My Dead Book, that process came pretty naturally. I wasn’t sure that it was going to work. It really did feel like a crazed experiment at some points. My friend Emily Hall, who wrote The Long Cut–she and I do a thing called ‘Pencils Down’ where we send each other our work. I’d sent it to her toward the end–though I didn’t know it was the end–and I was like, I think I’ve ruined it. She was like: No. Stop. It’s done.

But when we were talking about fragmentation, I said–part of me feels more at home, because I feel like the world caught up to my brain. I have never experienced things as a seamless narrative. When I have, I’ve usually experienced that as somebody paving over the details of my life or my story that don’t fit. And I would say that not just of me specifically, but of all the people that I’ve known and loved–their lives have been… the cracks get papered over by one seamless story.

Cole: You’re talking about how you don’t experience life as a seamless narrative–to take a loose stance here–I think that’s the case for many queer people. When you’re always in this fractured existence of, maybe, having a public self and a private self, of having different ways you need to behave for different audiences. It’s a sort of active editing of your life.

That’s something that the narrator experiences quite often and often reflects on. Dating as a performance, conversation as a performance. It’s all part of this queer thread that makes your experience of time quite disrupted from linear extension into the future.

Nate: It definitely feels queer. One of the things the narrator does multiple times in Ripcord is sort of tease at, or make fun of authenticity. And for a certain type of queer person, because there’s so much performance, there’s sort of no terra firma sometimes.

When people talk about authenticity, you’re like, When? Where? What do you mean? That seems like a wild luxury for a lot of people. You’re like: I’ve spent so much time code switching, or trying to fit in or background myself in a situation. Just basic survival things when you think about it.

This is both long ago and not long ago. I remember living in Seattle when I was 21–the city was kind of a sleepy city then, which seems wild now. We had an appointment with a landlord, my boyfriend and I, and I said to him, I’m gonna wait in the car and you go in because you pass. If I go in there and open my mouth, we’re not gonna get this apartment. And these were just regular conversations. It wasn’t a shocking thing–it was just matter of fact. For me then, that was authentic. It was me being really real.

I think a lot about the idea of performing and continuity, that it can be hard to have personal continuity. There’s a way for me where identity is always a bit of a joke, or a bit absurd. I ran into some I hadn’t seen in a long time and they were like, Oh my God, your beard, blah, blah, blah. And it’s so funny to me, because it just feels like another fake itineration. Let’s put on the middle aged man costume and go out.

Cole: I call it my girl drag. I’ve had jobs for years where for years I’m like–okay, if I’m a she/her to you, then I’m also a she/her to you. So I’ll wear my girl drag until I close the deal or whatever it is I have to do.

Nate: One of the things I wanted to do with the narrator was to show someone who has difficulty having those moments of downtime. This isn’t someone who ever gets to rest. I’ve known many people like that and I’ve been that person at different times in my life, where there’s an inability to really show up for other people. And that just becomes this endless performance.

That’s part of My Dead Book–in that book it’s actresses in older films. There’s a way in which all of these gay men from different periods of time have their echolocation. A performance artist or a band or whatever–it really was their way of finding some toehold in the world. We all make fun of it–gay men and their divas–but I think there’s something real there. It’s some way to throw something out into the mirage of the world that you can walk toward.

Cole: I want to come back to sort of the sequence of how these books arrived. I was so excited that Ripcord was a sequel. How did the books come to you in sequence?

Nate: I finished My Dead Book, and the publication for that happened really quick because I’d gone through a lot of rejection with another piece of work, and I knew that I probably couldn’t go through that process again. Which, I know–everybody in publishing is like, you’ve gotta just keep throwing yourself out there–I just didn’t know if I could do it.

I showed it to Matthew Stadler at Publication Studio, cause we’d been in conversation and I knew him from long ago. He said, I really love it. What do you want to do with it? And I just said, would you publish it? He said, sure.

Then it came out and, and after that it had its life in with Pilot Press that next year. But I started working on Ripcord in January of 2022. So pretty much right after the book came out, I jumped into Ripcord. Strangely, I think part of it was that while I was writing My Dead Book, my younger brother died suddenly.

I just wanted to keep going. There was a part of me that was like, I don’t want to think. So I jumped into working on it and I had stuff that was sort of leftover. With Ripcord, I was thinking, well, I really want to write about–because so much of the other book was death and memory and grief–I thought, I really want to write about work and about sex.

And not that this was anything new, but there just happened to be a period of time on social media then that was very much, like, no kink at pride. You know–there was anti-sex, anti-age gap stuff left and right. So I thought, I’m going to put a middle aged sexual body right on the first page. And once I had that first line–this was true with My Dead Book too–it was like, I had the first line and I had the last image of the book. So I knew how Ripcord would end.

My writing process is so integrated into my life. I don’t sit down at a desk and do it. It really is like I’m writing on scraps of paper, I’m writing in bed. I think I kind of write behind my own back–I sort of trick myself into it. Then suddenly there’s a lot of material and I’ll think, Okay, now I can do something with this.

Probably two years ago, I did do an essay–and it was so hard. It’s been so many years since I’d done anything like that. I was sitting down facing, you know, this blank page. I’m like, Oh, this is impossible. So once I started letting go of that, and I was taking a walk, going somewhere and jotting down some notes, I started to have something I could work with.

And that’s when I realized, so much of this is just intuitive for me. The more I sort of stay out of my own way, the easier it happens. I finished Ripcord, and I finished a third book, which will be the last of this cycle. That’ll be out in a year or two.

Cole: It’s so beautiful to hear you talk about having such an intimate practice with your writing, almost like it happens intuitively–in motion. In other interviews you’ve talked about riding on buses, and being in transit, in motion.

It sounds like writing is embodied for you in a certain way. Obviously you have to be focused on it–it’s not movement or performance in a literal way–-but it sounds like it’s really integrated into how you are as a person in motion in your life.

Nate: I do think there’s a level of performance or acting to it. And that feels exciting, because I kind of need to make myself not feel in control of it, or completely the author. I really look at the reader of My Dead Book and Ripcord and, and what will be the third book, Bastards, and they’re the coauthor–in a way that we all are when we read a book where you’re having a relationship to it.

But I think fiction, especially novels, do a thing with consciousness that you can’t do in other mediums. It’s sort of like a car chase in a film. That’s such a film trope. Consciousness is maybe that for the novel.

I also feel like the work is smarter than me. And I feel like the readers are too. So there’s a level where I just feel like I’m in good hands. I can go up on the high wire and go again, because there’s something there. There is some sort of net.

Cole: It’s interesting to hear you talk about intuition, because that’s a thread that feels really important for me as an artist. Reader as co-author–there’s an implicit trust there.

Nate: I feel that so much from seeing performances. You’re aware as an audience member when you’re in a good audience. When you can feel that there really is an exchange of information happening between the performer and the audience. That’s a dynamic I’m very conscious of when I’m writing. Trusting the audience is good

Cole: Last night, Dylan and I were at St. Mark’s church, attending a performance by Niall Jones, which was awesome–and a really good audience. And, in May of last year, Eileen Myles was hosting Pathetic Literature Happening at St. Mark’s church for the publication of Pathetic Literature, which you have a piece in.

I wanted to ask you about the centrality of friendships in Ripcord, in your work, in your life as an artist and a writer. I know that you and Eileen Myles have been in conversation with each other before.

Nate: Yeah, I interviewed them when Cool For You came out, which was in 2000. And I was so nervous, I remember–it was on the phone–and I was so nervous that I remember sweating through the shirt that I had on.

COLE: Relatable.

NATE: I’d been reading them since 1990 or something, so I was just scared. Of course they were lovely and amazing, and came to town, and over the next year we just evolved a friendship. We usually talk on the phone like once or twice a month.

They’ve seen so much of my work, and at times when I had truly lost faith in myself been very, very supportive, and always hooked me up with opportunities and readings. And you know, no matter how disastrous I could be [at a reading]–to be followed up one or two readers later by Eileen, who I think of as a combination of Johnny Appleseed and this amazing flaneur–I could bomb before that.

The friendships are really central to this whole cycle. These three books are really about that, whether it’s people that are alive or not. And not so much keeping someone’s memory alive, but just realizing that we’re all an amalgamation of all these different people that we’ve experienced and known. I just consider myself such a composite of everybody that I’ve known that it would be bizarre to me to not think of them.

This interview was conducted via video-call in October of 2024.