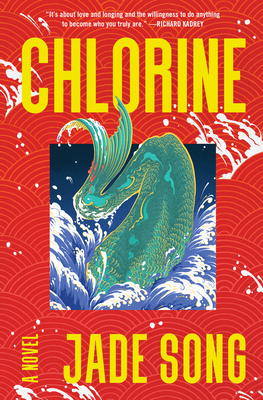

Sink or Swim

A Review of Jade Song’s Chlorine.

by Cole Stapleton

How much longer until we’re done growing up?

How much longer until we’re done growing up?

Eruptive tragedy and sinking failure feel like an inevitability these days. We’re waist-deep in the worst of history–and the water is rising. How long do we force ourselves to tread before we letting ourselves slip into the tranquil depths below?

In Chlorine, Jade Song tells the story of Ren, a star swimmer in a Pennsylvania suburb who lives with her emotionally distant immigrant mother. Ren is, for the most part, a normal high schooler; she dreams of taking home gold at nationals and earning herself a college scholarship. But she keeps a queer secret tucked under her swim cap: more than anything, Ren wants to be a mermaid. And she is willing to go to distressing lengths to make this dream a reality. Song’s characterization of Ren speaks to a larger theme emerging in the voice of the Zillenial writer. It is a decision to detach rather than reckon with the vast systems of cruelty we’ve had thrust upon us. We don’t want to analyze from above to fix what’s broken; we’d rather remain submerged in fantasy.

The supernatural has always been a realm where storytellers could explore the hidden currents of normative society. The werewolf is driven by his lusty animus, only revealed in the romance of the moonlight. The vampire brazenly bares her fangs and her desire. With Chlorine Song joins the the contemporary traditions of Buffy and Twilight–taking a moody monster-movie outsider and placing them in math class, pitting the occult against the mundane. Today’s monsters define themselves in opposition to their canonical portrayals. Ren rejects Ariel and the gendered connotations that come along with the clamshell bikini. Finding satisfaction in her bulging muscles and efficient body, Ren is decidedly more butch. In crafting her own mermaid mythos, Ren explores the edges of her humanity. “Back then, I was a girl, a body of water, a liminal state of being, a hybrid on the cusp of evolution.”

Ren’s story is steeped in the influence of her swim coach Jim, the belligerent perv who singles out Ren early in her swimming career. Jim lusts brazenly after Ren and the other adolescent athletes under his care, all the while whipping them into his own pod of hormonal acolytes. One of Chlorine’s strengths is the relationship between these two characters – one of the most central in the book. Ren is aware of Jim’s creepiness and even seems bored by the predictability of their positioning, but the gravity of their relationship remains sincere. How can an athlete achieve without the punishing demands of their coach? Discipline is one of Ren’s most compelling fetishes.

While Ren’s internal voice is often clear and biting, her connections to the people around her are murkier. Her relationship to her parents and to her wider community barely penetrate the surface of Ren’s emotion. Ren is positioned as an outsider on the swim team; with a disaffected tone she recalls how she navigates to the top of her game. Ren’s sense of withholding superiority prevents her from forging meaningful relationships. As a result, the most compelling characters in Chlorine are antagonistic; companionship is starkly absent.

All the while, Ren’s admiring BFF Cathy waits patiently in the wings for Ren to realize her affections surpass friendship. The sapphic curve of this relationship seems mutual, but where Cathy’s desires are more straightforward, Ren remains mired in pursuit of a mermaid’s impossible perfection–and whatever affection Ren does cede to Cathy is begrudging. In a series of letters that Cathy writes to Ren via message-in-a-bottle, we see how callously Ren has treated her throughout their friendship: relying on Cathy as her solitary emotional support, then cruelly ignoring her for an entire summer. Ren shares a similar lack of empathy for her mother, who has raised her as a single parent following her father’s unceremonious departure to his home country of China early in the novel. While Ren’s suffering isn’t unique among teenagers, she metabolizes it toward extreme ends. This pain is the justification for Ren’s insistence that her own feelings are the only ones worth considering.

BUT – this bottomless capacity for fantasy and melodrama is what we love about teenagers! And in Ren, Song finds a worthy subject. Chlorine has a number of YA hallmarks – first and foremost its construction as a classic bildungsroman. Chlorine is deliciously predictable. Yet where another story might have seen Ren mature and grow out of high school fantasy, Chlorine subverts this tradition. Ren stubbornly refuses, living out her mermaid fantasy rather than actually come of age.

On the reflection of the water’s surface we see a mirror to ourselves. We love to read about teenagers because in their homes and families and bodies they are as trapped as we feel. And as Zillenials graduate into the catastrophe of the 2020’s, the mermaid is a perfect image onto which we can project our subaquatic desires. Mermaids capsize power structures by enchanting sailors to their deaths; singing from the depths, they thrive in impossibly inhospitable conditions. We can’t flip a fin and swim away from all our problems on land, but we can exchange our childhood fantasies for much darker, adult ones. Ren understands what the rest of us have come to know through the decades of upheaval in which we’ve grown up: transformation comes at a cost. But something’s gained. We know firsthand the power of metamorphosis, and its pleasures.